AIRBORNE RANGER

Fast, Open-World Action from a Simulation Company

In early 1984, my father bought me a Commodore 64 for my 12th birthday. By the time I was 16, I had written a few games, played dozens and grown smitten with most of the latter, often while figuring out how to play them. They were on disks that I had trade-borrowed from classmates and copied. My almost valid rationalization is that I wouldn't have been able to afford them anyway.

One thing that had become apparent during this period of almost-free playing (blank floppy disks weren't cheap, after all -- just much cheaper than non-blank ones) was that MicroProse Software was the master of simulations. While every electronic game is a simulation of some kind, if you're in the mood for a deeply involved representation of what it's like to, say, pilot a fighter jet as you locate and take out enemy structures, and you don't mind a bit of math, this company has you covered.

Yes, one peers through his televised canopy at a frame rate by which he can time an egg, but graphical flair isn't the point. The visuals are, again, meant to represent what a pilot sees, and plenty of attractive, less active screens can be called up anyway: detailed maps, information about the jet's condition, etc. For the most part, simulators offer cerebral fun, not visceral; and indeed, I enjoyed F-15 Strike Eagle at the time, and I still return to it on occasion. Other admirable pseudo-games from the eighties include the chopper simulation Gunship and the emulated submarine battle Silent Service.

I've mentioned being 16 because that was when I first had an over-the-table job. Minimum wage was $3.35 per hour, and after bagging a couple weeks' worth of groceries at a store called Albertson's, I was thrilled to receive a five-figure paycheck. The last two figures might have been cents, but still: $159.00 and change felt like a fortune after years of relatively meager lawn-mowing allowance.

Thus began my years of acquiring software from actual stores, at least most of the time. The only disk that I'd previously purchased had been the impressive Skyfox by Electronic Arts, for which I'd saved up. Oh -- I'd also been given Infocom's masterpiece Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz along with the C64, and Synapse's superb conversion of Zaxxon by a family friend.

Anyway, never having driven solo beyond Albuquerque's West Side, I asked Dad if I could take the truck into the Northeast Heights (closer to the mountains) come Saturday. He approved. I wrote out the directions as he dictated them, his every intersection lovingly punctuated with "and be careful."

The objective of my mission was, uncharacteristically, the mall: a place inside which I'm happy to say I haven't set foot in over twenty years. At the time, however, Coronado Shopping Center harbored two Lands in which I'd never been free to roam with a ton of spending cash: ComputerLand and MusicLand.

Deep Purple's album Machine Head -- on cassette, of course -- helped me to make the twenty-minute expedition to the Lands of computer games and rock music. For the previous few months, I'd been watching a low-quality VHS copy of Pink Floyd's film The Wall, initially borrowed from one of my disk-trading pals (thanks again, Anthony). I decided that I needed the commercial release, so I bought that. I walked a few stores down and looked over games before falling under the impression that the description and screen shot on the back of the Airborne Ranger box promised a purchase I wouldn't regret.

Something by MicroProse? Well, why not?

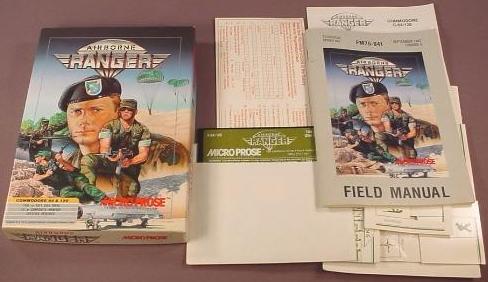

I got it home, tore off the shrink-wrap and read the instructions (Field Manual, I mean) cover to cover. I've always been a manual-reader anyway, going back to early '82 when I first became obsessed with Atari VCS games. I don't want to miss out on anything, y'know? Even more convinced that I'd picked up something great, I excitedly placed the included overlay onto the keyboard, switched on the computer, inserted the disk and loaded up the game -- for a game it turned out to be, even if it contained simulation elements.

After a tentative session or two during which I came to grips with the keyboard controls (the joystick part was perfectly intuitive: Move my Ranger around and / or fire the selected weapon), I played and played and played. I had clearly decided correctly on how to spend thirty-odd paycheck bucks. I couldn't have had more fun.

To this day, Airborne Ranger is one of my C64 favorites. Granted, I have many, but not for nothing is this among them, and I revisit it every year or two -- more than three decades after that slightly nerve-wracking but also exciting first trip to the Heights.

To give you an idea of MicroProse's approach to this 1987 release and how it differs from the actual simulations, I'll read you an excerpt from the final pages of the Field Manual. It's a bit snotty about the arcade-style action games we love, but let's keep in mind that the company aimed to stand out amongst the many others by providing experiences that vastly differed from the norm. This section of the game's included book is credited to the "Airborne Ranger Design Team," but it was allegedly written by Lawrence Schick (see below) on his own. The following quotation is used for academic purposes only. No copyright violation is intended. I've even cleaned up some of the grammar and punctuation for him. He's welcome.

One day in early 1987, "Wild Bill" Stealey, President of MicroProse, came into a product-development meeting and said, "Let's do a fast-action, easy-to-learn combat game called Airborne Ranger, in which one soldier is pitted against lots of enemies!"

"An arcade video game!" we screeched. "Bleahh!"

"No, not an arcade game, but, uh, a combat-action simulation! Yes, that's it!" he said, pounding the table. (That always gets our attention.) In short order, he convinced us that we could do it: We could create an intelligent, fun, suspenseful, arcade-style -- uh, we mean fast-action -- game that would appeal to fans of our usual intense simulations as well as devotees of you-know-what games. Gamers everywhere were waiting for this! It was our duty to them that we start immediately!

So we did. We formed a design team consisting of Lawrence Schick (game design, project management), Scott Spanburg (software development) and Iris Idokogi (software graphics) [along with Ken Lagace, who created the sound effects and music]: all designers of "serious simulations," but also veterans from other companies where we'd worked on -- you know -- action games...

As it started to come together, we realized that Bill was right: This was going to be a fun game.

The player can assign a Practice Ranger, for whom he chooses one of the game's twelve missions and four difficulty levels; but his success, statistics, promotions and medals aren't saved. Going with a Veteran Ranger requires a data disk and entails a sequential campaign through all missions, after which they're available indefinitely (as with the Practice Ranger, except with saved, cumulative stats). I remember devising "funny" names for the men on my disk: Unbeeta Bill, I.M. Kickenass, Inna Suntu Long.

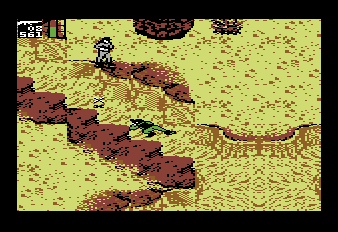

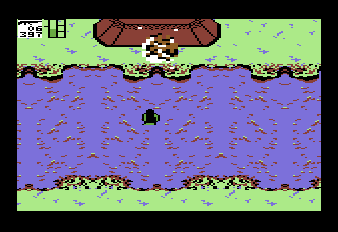

The perspective is slightly three-dimensional from above and directly behind. The Ranger, who can roam in any direction around the massive overall combat zone, doesn't remain stationary in the center as the terrain scrolls, but enjoys a generous area around it. Each mission takes place in either a Desert, Temperate or Arctic environment, thereby featuring particular obstructions and natural hazards.

These can all be exploited: taking cover behind a boulder, bush or wall, for instance, or luring an enemy soldier across a weak spot on a frozen pond. There are minefields to mind, tree-trunk mazes to navigate and barbed-wire entanglements to breach with grenades.

Your Ranger can always walk or crawl; running depends on his current level of fatigue, shown in a gauge and influenced by any wounds he's sustained and how much he's carrying. It returns from the red zone to allow more running only after a rather long break for slower movement. The controls are actually brilliant: He can move in any of the standard eight directions, but the crosshair that permanently floats in front of him shifts between four positions along his every eighth of a heading. Simply put, it quickly but precisely moves through these spots before he rotates to face his next direction. Fine-tuning works wonders for programmers, doesn't it? The balance they've achieved here is almost uncanny.

As a mission begins, a distant, bird's-eye view of the area (a version of the map) scrolls by. You pilot a southbound plane, dropping three Supply Pods that your Ranger will retrieve for extra ammunition and first-aid kits. It's best to stagger the Pods, as their total ammo exceeds what he can carry at one time -- and again, minimizing the weight of his gear will enable greater running distances. As you steer the plane horizontally, bare ground should be targeted. Pods that land on anything else won't survive. Neither will your Ranger, so after the plane has reached the zone's southern edge and you've shoved him out to the sound of the buzzer, it's crucial to direct his parachute carefully. Touching down in a trench is especially slick.

The first thing I do after my Ranger lands and the view magnifies is to consult the radar-like map (which helpfully pauses the game) and ensure that the Pods, now represented by tiny Xs, have all landed intact. The width of the enemy territory fits on screen, but not its length, so the map can be manually scrolled to the north and south.

Now I plan my route from Pod to Pod along an imaginary line drawn between the ends of the numerous trenches. Crawling along these whenever possible will keep hostiles from knowing I'm there until I want them to. It's fun to pop into a standing position with a space-bar press and greet a soldier with a machine-gun burst. "Surprise! Goodbye, too!"

It's also a blast to run up to one of the installations encountered along the way (my route also takes a lot of enemy destruction into account) whose occupants have audibly been trying to gun me down, arm a more destructive weapon and take the place out with a fulfilling BOOM.

The uses of the Ranger's various weapons are divided nicely between your numerous potential targets. Missions dependent on stealth require a lot of knife-play, as you'll fail if you prematurely alert the bad guys to your presence. When you can be noisy, it's nifty that gunfire and explosions draw soldiers toward you. In such missions, those guys are best dispatched with your automatic carbine rifle. "Thanks for dropping by! Thanks even more for dropping dead!"

Regarding the installations, brick machine-gun nests and other relatively weak things like tents, guard houses, land-mine patches and multiple troops can be destroyed with grenades, which are thrown farther the longer the fire button is held. Hangars, concrete bunkers and other strong buildings are wiped out with time bombs or rockets.

Firing any of these explosive weapons will return the carbine to your character's hands immediately afterward, which is handy indeed. An entry can be shot into the occasional structure (an Airborne Ranger doesn't "try" doors), which can be pillaged for ammo before it's annihilated completely.

The Ranger briefly falls when he's shot, and depending on chance and difficulty level, he may suffer one of three wounds, each of which can be manually healed with one of his precious first-aid kits. When all three indicators are white, he's an ex-Ranger. Death can occur instantly if he wanders onto a mine, gets rocketed by an automated mini-tank or meets with one of the grenades carried by enemy soldiers on all levels but "Easy."

As each mission proceeds, a timer counts down to the plane's return, but the limit is always fair, provided that you don't tarry too much. You can hear the plane's approach from anywhere, although the noise is easy to mistake for a flying electric can opener. Your objective and pick-up point always lie at the northern end of the zone. The missions are appealingly varied; to mention just a handful, you might capture an officer, create a diversion by blowing up as much stuff as you can, or obliterate a radar array or fuel dump. My favorite description of targets includes an "explosives magazine." A magazine about anything should be easy to destroy, right?

In stealth missions, you'll steal a code book, photograph an experimental aircraft or free prisoners of war from barred pits. What's cool about the latter operation is that your success returns to the roster any disk-saved Rangers who've previously run out of time and ammo and therefore gotten captured.

The plane can be recalled early if you've fulfilled your objective with time to spare, but I tend to enjoy standing near the pick-up point and eliminating any last-minute troops who have the nerve to attack me. One usually runs out of time before ammo, so it's satisfying to increase the body count when the requisite goals have assuredly been met, particularly when one is playing the floppy-recorded part of a Veteran Ranger.

Don't let your conscience bother you out of slaying hostile soldiers, by the way. Some of them are so dumb, on the easier difficulty levels anyway, that they're much better off dead. "This wall can't possibly have two sides!" "I know I heard an intruder walking around here somewhere! I think I'll stand still near this dark trench!"

Yet another seems to say, "I've found you! Now to drop to the ground right in front of you!" They can hit the deck like your Ranger can, you see, but the times they choose are often accidentally funny.

Airborne Ranger boasts a satisfying balance between action and strategy. The huge number of details that its creators thought to include, the assortment of distinct missions, the glorious randomness of everything and the freedom to improvise one's own route combine to make it persistently compelling. Several years after pitching the accidentally torn keyboard overlay, I remember what to press to do what. Even if I didn't, the Field Manual survives. This is fortunate, as I clearly recall my attempts at working out how to play those games I obtained unethically in the pre-Albertson's days.

Even now, learning how to play an unfamiliar game whose emulated file I've discovered can take a lot of trial and error, fun though the process might be. If it can't quite be done, at least instructions are available online these days. I used to find myself talking to fictional bad guys through my character: "Leave me alone! I'm trying to figure out how to control myself!"

Other versions of the game were issued for the Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum and DOS PC. A firm called Imagitec Design converted it for the Amiga and Atari ST in 1989. The C64 game is the only one I've played, but if the same care was put into the others, it's pretty safe to say that they're worth one's time. A sequel by Sleepless Knights / MicroProse came out in '92 for the latter three platforms above. It's called Special Forces. I haven't tried it, as I'm not into indirectly directing multiple soldiers at once. It feels like homework, to revisit the subject of simulations that involve math. Airborne Ranger feels like recess. With weapons.