Games That You Should Try Again

UP'N DOWN

When you play an old video game, you accept its unique, autonomous world. There's no need to take realism into account; it's a wonderfully irrelevant concern.

The reason I prefer games from the '70s, '80s and early '90s -- aside from the constant innovation and the wildly creative risks -- is that every one of them knows it's a video game, so to speak. It provides an experience that's literally impossible except in Game Land.

Even a game that's clearly meant to make a driver out of the player exhibits a world of its own, physical behavior included. It's a beautifully blocky, imagination-firing environment, incomparable with any other. Unreservedly serious attempts at simulating activities that are much more fun in real life -- playing sports, driving cars, performing music -- are thankfully not found among the thousands of classics, regardless of what some ads might have claimed back then.

I've enjoyed several online discussions with Kirk Israel, who home-programmed the Atari 2600 game JoustPong (later renamed FlapPing for legal reasons). At one point, he was able to concisely articulate what I've been going on about. I quote with his permission:

"The appeal of old games has always been their self-contained aspects. Each cartridge in the large collection that I lucked into contains its own microcosm, with its own creatures, boundaries and rules of physics. The eponymous Superman of the Atari game isn't just a reflection of the muscled, flying hero of the comic books. He's a new, pixel Superman, fighting crime in his limited pixel world, jailing pixel Lex Luthor and getting kisses from pixel Lois Lane. For this particular Superman, this is the full extent of the world. The advantage of this less literary, more literal approach to game story is that it embraces the limitations of player action; it doesn't have to explain them away."

As a case in point, even a couple of scrolling, sky-view driving games can be enormously dissimilar. Last night, I fired up MAME and played the 1982 arcade game Bump 'n' Jump by Data East (released here in the States by Bally/Midway). I'd thought of it for no particular reason and realized that I'd never given it a fair shake.

It's not...awful, but I certainly rediscovered my reasons for having avoided it over the years. After the player's vehicle bumps into another, he's robbed of control for about a second. This makes the game-play consistently annoying, as there's a whole lot of bumping going on. His certainty that he's made the right move to avoid, say, a rocky outcropping, makes for excessive frustration when he watches his car crash anyway because of the controls' failure to register.

Recognizing a significant blemish that would have merely required a bit more polishing is disappointing; the game could have been a lot of fun. As it is, it simply doesn't feel good to play. This shows us afresh how far fine-tuning can go. Seemingly small details add up to hugely impact the fun level.

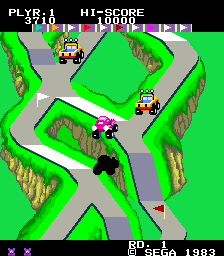

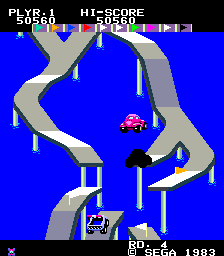

Proof positive: I then recalled the existence of Up'n Down. That might look like a funny way of putting it, but one doesn't read or hear much about that '83 Sega arcade game. In spite of its several home adaptations, it floated humbly past, an overlooked, Zen-like piece of driftwood slipping between the big-splashing games whose ripples remain today.

My unmerited disregard for it was surely buttressed by my mistaken assumption that it strongly resembled Bump 'n' Jump, even allowing for the latter's bird's-eye perspective as opposed to isometric. In truth, the elements in Up'n Down are impeccably balanced, making it a joy to play. And that's not the only difference.

For one thing, the player's vehicle can't knock another off the asphalt. It can still destroy one with a deftly timed jump (well, landing), but there isn't even room on any of these narrow roads for two adjacent cars. Death approaches not from the sides, but from the front and rear, and the player's survival depends on his mastery over acceleration and deceleration, both on the ground and -- however briefly -- in the air.

Speaking of the slimmer roads, there are always two or more on screen. In fact, one of the many things that I dig about the game is its abundance of forks (and I'm not talking about the kind that would be required for actually eating one of those giant servings in BurgerTime). The player recurrently finds himself called upon to make a split-second decision about the route he wants to take. The available tactics surpass the simple vehicle-dodging that's characteristic of most driving games; this is no race. Everyone else you see is just sort of...out and about.

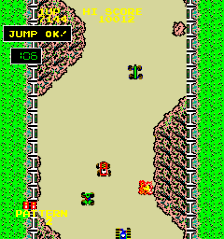

Bump 'n' Jump only provides the one road, of course. Apart from the player's bounding facility and related death-from-above powers (the other vehicles are ground-bound in both games), the only similarities between the two are the variable driving speeds, the vertical scrolling and the level separation. The levels are called "courses" in Bump 'n' Jump and "rounds" in Up'n Down. In the latter, the landscape steadily changes quite drastically, its very shape contributing to the gradual rise in difficulty. Even on its own, this playfield variety would make Up'n Down the more consistently compelling game.

While it's true that in each case, you're in a car that can jump -- but which somehow still can't float -- destroying other vehicles is not your primary reason for exploiting this ability in Up'n Down. That's merely a cool extra. Apart from the obvious collision avoidance, you're chiefly leaping to switch routes when you don't like the one you're on. This can be done whenever a separate road happens to bend perfectly in line with your heading. Then it's just a button-press to hurdle the median in between. Whatever mechanic serviced this vehicle, I want his card!

Your grounds for frequently changing roads: Ten flags, each unique in color, wait for your car to run them over. Such is the life of a flag in this particular world. When you've thus turned them all white, you've beat the round. In Bump 'n' Jump (what is it with driving games and their companies' reluctance to fully spell "and"?), your only real objective is to survive until you've reached the end of each course. I reached the end of my rope long before that. I only played beyond the first course so the screen shot above wouldn't display a pathetic score. Even loners can be competitive. And I'm damn good. Choose your game; I'll gleefully thrash you. Yes, I'm deliberately provoking.

Most significantly, the game that I'm actually writing about does feel good to play. My realizations that I liked it a lot and that I was really getting into it were entirely unexpected. It really hooked me; and for a driving game, it's extremely original. I'd neglected it for years! I'd never played long enough to fully understand the mechanics. Once I had, I found myself trying to figure out all of the details behind its deceptive simplicity. I now present you with the results of last night's obsession.

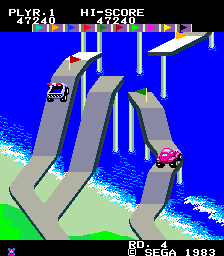

Each round repeats indefinitely until all of the flags have been nailed. There's a huge number of available route changes, via both jumping and merely veering, and almost every flag is colored similarly to another (even if no two are actually identical). So, happily, spontaneous decisions are favored. Memorization is out, unless you play the game a lot.

Another coolness is that the player isn't forced to drive forward. He can actually back up. It gives him an uncommon degree of control over his car, and it definitely makes the game more fun than any other firepower-free road trip. There's a lot of strategy involved; you're given time to decide where to go, so you don't have to favor full speed to do well just because it's a game with cars in it.

The car can't jump backward while it's already in reverse, but it can start backtracking with a rearward leap. When I used to give up on the game after taking the occasional quick stab, it probably didn't occur to me to try backing up at all. It certainly became a whole new game when I happened to try doing so last night. The ability to reverse in a vehicle! Who woulda thought?

You don't get away with prolonged backtracking, of course -- other vehicles soon approach, especially in later rounds -- but it's a great way to time your jumps when you're feeling destructive, and a great concession that you can change your mind about which road to take, provided that you haven't driven too far past the divergence or divider. It's also an obvious way to avoid rear-ending a slow vehicle (elderly people shouldn't be permitted to drive, at least in Game Land), in the event that you haven't built up enough speed to jump onto it.

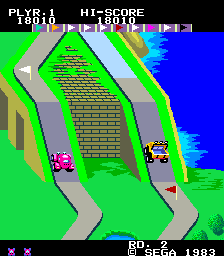

That leads me to the occasional requirement to throw 'er in reverse for a second: While most of the inclines pose no difficulty, there are some hills that you'll want to meet with a lot of momentum, unless of course you get a kick out of seeing your car roll helplessly back down after an earnest halfway climb.

Those other drivers must be blind or suicidal. It's 1983, so there's no chance that they're looking down at those stupid cell-phone things. In any case, they'll cheerfully drive right into you, so you'll have to be the responsible one out there. You won't see any fender-benders on these roads; any vehicle that so much as taps another will immediately explode. You'd think that these guys would spring for stronger bumpers before driving in such a hilly, erratic part of town. The player's car flies apart even when it lands in grass. How it can survive landing on a tank-sized mutant Jeep is anyone's guess. Thankfully, an extra car is acquired whenever the score increases by 10,000 points, as long as the game's default settings haven't been changed.

Presumably, each of those light-gray road sections is a perfectly rectangular patch of ice. Such an oddity is certainly in keeping with the generally bizarre environs. And just like ice in real life, it gives your car an abrupt burst of forward speed. (Hey, the Sega people never claimed to be physicists.)

Speaking of ecological peculiarities, gigantic food items often appear on the roads. These represent the type of awesome, game-only experience that doesn't instantly spring to mind among alien-world exploration and dungeon-monster blasting: driving your car through a massive ice-cream cone. Thanks to those Sega visionaries, it doesn't even need a wash afterward. You just get a lot of bonus points.

Another strength is that the viewpoint is isometric because it has to be. It's not based on a gratuitous decision: "Let's show off how we can almost make it look 3-D!" It wouldn't be the same game in any sense if its perspective were directly top-down.

One has to wonder why it's so important for this driver to collect a bunch of flags in the first place. Maybe he's planning on opening his own embassy! Hey, everyone has his dreams. I guess this guy's just too cheap to shop at the embassy-supply store.

Looking at the playfield might lead you to believe that the controller has to be moved diagonally, but this isn't the case. Forward and backward control your car's speed, and simple leftward or rightward movement determines your choice of road beyond each junction. There's also a button for jumping, of course.

Don't give up after just a game or two. Doing well entails practicing until you've grown nimble at the controls. While that's true for most any game, the most important thing to remember here is that you can save yourself if one of the other autos is fast approaching from behind and you don't have time to accelerate sufficiently. Just pull back on the joystick and push the button, and you'll hop backward over it (or onto it). Also keep in mind that your car will magically reverse in midair if you tug back early enough. This is handy when you realize that you're about to overshoot the road you're aiming for, heading instead for the grass beyond. Granted, it's a gas when you land perfectly in one of the ponds that sporatically crater the terrain; but even if playing miniature golf with a car is an interesting idea, you don't get any points for sinking it.

Maybe the reason we don't hear much about the game is that it possesses the dumbest title ever to adorn a cabinet marquee. It sounds like a fifth-grader's sexual term. Even when the game was new, people probably didn't want to tell their friends that they were trying to improve at it. That could have made for some clumsy conversation:

"I'm gonna go play me some Up'n Down, if ya know what I mean!"

"I sure do! Har, har! Ya mean the video game."

"Of course. What else would I be talkin' about?"

"Exactly. I can't think of a thing."

It was released near the end of a period during which Sega released other widely home-converted isometric games, such as Zaxxon and Congo Bongo. The idea of driving over flags probably came from Namco's 1980 coin-op Rally X (a Midway game over here), but that's a graphical superficiality; they could have been pineapples or trousers or dogs. The games are nothing like each other. I wish that the Up'n Down programmers weren't anonymous in typical Japanese fashion, so I could praise them by name for their inventiveness and their resolve to carry out suitable fine-tuning.

I admit that I also wish my on-screen counterpart would turn down the stereo in his car. It plays the same annoying instrumental over and over.

Chances are, many games that you've played only briefly before turning your back on them are worth returning to in earnest. Forget nostalgia and give yourself the present of adding enjoyment to your present. Plenty of old games out there -- or inside your emulation directories -- could easily become new favorites. They're just waiting for you to come and play.